I am infrequently cheered by any book published on contemporary art, most of which seem to me consisting of oddly insipid cocktails of snobbishness, bullying, philistinism, and bluff. A spirit-boosting exception is the recent publication of the last volume of Leo Steinberg’s collected essays, entitled Modern Art. On the tremendous strength of his writing on two foundational figures in contemporary art, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, his contribution to the understanding of recent art is immense and widely acknowledged. Most of his substantive writing on these two was already collected in 1972 in the volume Other Criteria. But while he pursued his studies of especially Renaissance art, especially Michelangelo, as well as Picasso from the 1970s until his death in 2011, on a few occasions he also gave lectures on recent art, most substantively a lengthy reflection on Rauschenberg again that is included in the recent volume. What seems to have been his last word on the topic was a lecture entitled ‘Art Minus Criticism Equals Art’, which reviews some of his earlier work and then struggles and self-admittedly fails to understand, or at least to appreciate, the work of Jeff Koons. The lecture, now published as the last essay in the volume, perhaps offers a final, and indeed novel, insight into contemporary art. How might the admission of a failure to understand a prominent contemporary artist contribute to the understanding of recent art?

Recall Steinberg’s titanic struggle in the early 1960s to understand the work of Jasper Johns. In the essay ‘Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public’ Steinberg recalls his initial reaction to Johns’s first major exhibition in 1958: “I disliked the show, and would gladly have thought it a bore. Yet it depressed me and I wasn’t sure why. . . I was angry at the artist, as if he had invited me to a meal, only to serve something uneatable, like tow and paraffin . . . [but] the pictures remained with me—working on me and depressing me. The thought of them gave me a distinct sense of threatening loss and deprivation.” (Steinberg 1972, p. 12) He reflects on his initial reaction in light of Johns’s Target with Four Faces (1955), which presents a target painted in encaustic and largely occupying a two-foot square canvas. Atop the canvas is a shelf with four niches containing plaster heads, oddly cut so that what remains is the area from the upper chin to half-way up the nose. The mouths are closed and the lips expressionless. On top a hinged flap is raised, which if closed would cover the shelf and so also the faces. Steinberg begins to think that the sense of deprivation stemmed from Johns’s rejection of illusion, the transformation of physical paint into something that was not literally there; illusion in that sense is a constitutive part of the great tradition of Euro-American painting from Giotto to de Kooning. To accept Johns’s work as a signal instance of new art would then to accept simultaneously the end of something of inestimable value, the appreciation and study of which merits the work of a lifetime.

Yet after repeated viewings and reflection, Steinberg began to find the piece expressive: “And gradually something came through to me, a solitude more intense than anything I had seen in pictures of mere desolation. . . I became aware of an uncanny inversion of values. With mindless inhumanity or indifference, the organic and the inorganic had been leveled.” (ibid) He then notes a second inversion of values: the target is ‘here’, the faces are ‘there’, and this inverts our characteristic “subjective markers of space”. (p. 13) In his lengthy essay on Johns Steinberg went on to characterize Johns’s typical subject matter—targets, flags, maps—as “things the mind already knows” (p. 31) And when at the end of that essay he addresses Target with Four Faces, he asserts that “The content of Johns’s work gives the impression of being self-generated—so potent are his juxtapositions . . . As if the subjective space consciousness that gives meaning to the words “here” and “there” had ceased operation . . . What I am saying is that Johns puts two flinty things in a picture and makes them work against one another so hard that the mind is sparked. Seeing them becomes thinking.” (p. 54) So ends Steinberg’s account of Johns, and surely its reader finds herself thinking that Steinberg has shown a way of thinking that Johns is not just painting in a new way with new subjects, but also has re-invigorated artistic painting under contemporary conditions and tastes, including the audience’s taste for abandoning ‘illusion’ and with it the conception of the artist ‘magically’ transforming materials and contents, and instead offering something to its taste for a new kind of realism in subject-matter. Further, and deeper, Steinberg’s account shows a way of thinking about Johns, and with him contemporary art generally, as renewing under contemporary conditions perennial aspects of art. Kant, for example, had suggested that ‘aesthetic ideas’, that is, the contents of artworks, ‘give rise to much thought, without giving rise to any particular thought’. Or more specifically with regard to linguistic arts, Dan Sperber and Deidre Wilson have suggested that the ‘poetic effect’ occurs when an utterance induces “a wide array of weak implicatures’ (Sperber and Wilson, p. 222), that is, an unresolvable plurality of ways of taking what is uttered. In light of these suggestions, Steinberg’s conclusion could be put by saying that Johns has ‘sacrificed’ central and durable aspects of artistic painting in the service of renewing and fulfilling part of its aim, which is to present a painted artifact as a kind of ‘thought-object’ that does not convey a paraphrasable meaning, but rather induces and rewards repeated perceptual encounters and reflection.

In ‘Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public’ Steinberg went on to generalize his struggle. Recent art, he suggests, asks that one sacrifice one’s acquired tastes, while further offering nothing secure to guide understanding and appreciation of its novelty. It’s a function of modern art generally to create “a genuine existential predicament” (p. 15) for the viewer, so that there’s a quasi-Kierkegaardian ‘leap of faith’ demanded from the viewer in attempting to understand, appreciate, and enjoy such work. Nothing guarantees the success of the leap in even a single instance. What if one leaps, and there’s nothing there?

In his early 80s, Steinberg leapt again. In 2001 he was invited to give a talk in connection with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s show ‘From Jasper Johns to Jeff Koons’, whose contents were selected from the recently donated collection of money-bags Eli Broad. Steinberg hesitated, as he had given no serious thought to many of the artists in the show, and also didn’t like some of their works. Reassured by Broad himself, Steinberg went ahead with the lecture ‘Art Minus Criticism Equals Art’. Steinberg recalled his account of Johns and declared that it had been superseded by the work of Kenneth Silver, who found in Target with Four Faces a ‘homosexual thematics’ and the expression of a project of ‘mapping gay desire’. (Steinberg 2023, p. 158). Then Steinberg rehearses his earlier writing on Roy Lichtenstein and Hans Haacke, and notes that both are part of an urge characteristic of modern art towards abjection by “capitalizing on the pulling power of incompetence and low-level taste” (p. 167), a pull also evidenced to a heightened degree in Gilbert & George’s Naked Shit Pictures (the title tells you exactly what you need to know) and New Horny Pictures, which present newspaper ads of male prostitutes together with the posed photographic portraits of the two artists (pp. 168-69).

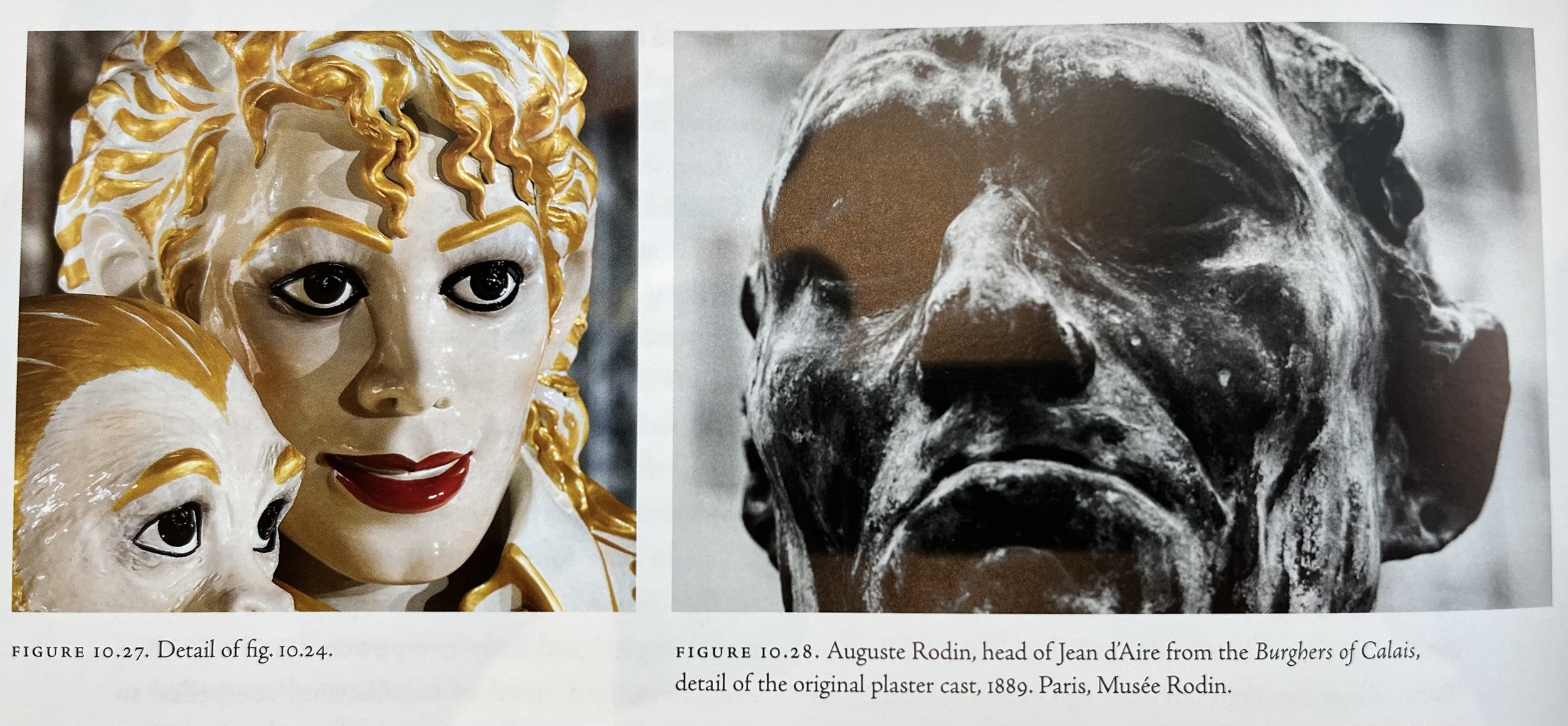

Steinberg then turns to a lengthy consideration of the hardest nuts of contemporary art, the work of Jeff Koons. Steinberg declares Koons to be a master in competitive ‘one-downmanship’, where the line of artists prominently including Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, and Gilbert & George seek to out-do each other in “promot[ing] a general degradation” (p. 169) Koons found the most insidious subject-matter, kitschy figurines in the 1980s and pornography in the early 1990s. Steinberg acknowledges his inability to understand Koons, and returns to his remark in ‘Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public’ that modern art continually shakes off its admirers, but with the difference that he now includes himself among those who have been shaken off. Is anything different about the case of Koons, other than that he could appreciate new art as a youth in his 40s and 50s, but not as a senex in his 80s? Steinberg recalls a remark from Jacob Burckhardt’s Cicerone that he had read in the 1950s on the effect of the concave fluting on an Ancient Greek column--“It suggests that the column thickens and hardens inward, as thought collecting its strength”—and says that the remark helped him see not just what the ancients had done, but also what art criticism could do: “you could stay with the outward form; or see all the way through” (p. 175). This ‘seeing all the way through’ becomes a fixed part of Steinberg’s taste, which “enjoys the complexity of simultaneous surface and depth more than in-your-face shallowness” (p. 177); the latter is of course Koons’s métier. Steinberg ends with contrasting close-ups of Koons’s Michael Jackson and Bubbles and one of Rodin’s Burghers of Calais, declares the contest “a standoff, a draw” (p. 177), and ends with a startlingly bland comment: “Michael Jackson and Koons make a good match: you can dance at their wedding, or go mope with Rodin. You can shuttle between them, to suit the occasion, your temperament, or the time of your life.” Well, I suppose you can.

But I would suggest that what you can’t do is to find a way of thinking about Koons’s work that makes it bear anything of the seriousness, complexity, and eternal provocation that one finds in countless instances of the world’s art over the past 40,000 years. Steinberg’s final remark seems to wish away the necessary sacrifice that is preliminary to any enthusiasm for Koons’s work, that is, the sacrifice of the skills and pleasures of expressive seeing, of sustained looking, of seeing depths within surfaces, and of much else. Perhaps it was not Steinberg’s declaration of a draw between Rodin and Koons that was his final contribution; rather, Steinberg’s contribution to the understanding of contemporary art was his lack of understanding of it.

References:

Jacob Burckhardt, The Cicerone (1873)

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment (1790)

Leo Steinberg, ‘Art Minus Criticism Equals Art’ (2002) in Modern Art (2023)

-----‘Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public’ (1962) in Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth Century Art (1972)

Dan Sperber and Deidre Wilson, Relevance: Communication and Cognition (1995)