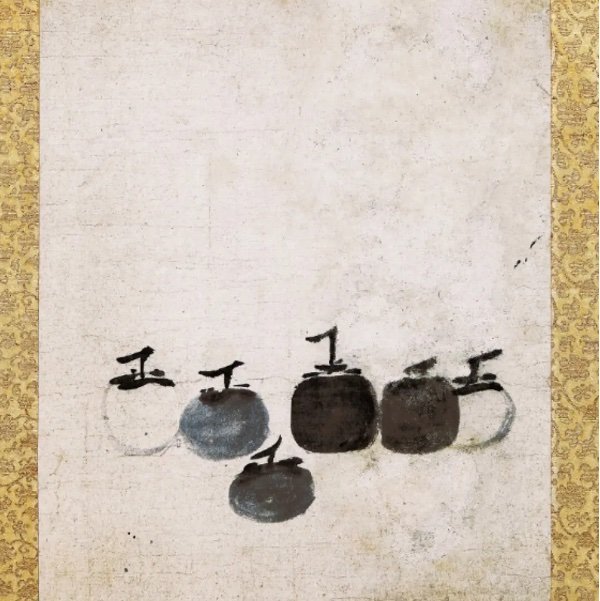

In my previous post I introduced the difficult thought that Muqi’s painting 6 Persimmons is about ineffability, that is, our pervasive inability—in our perceptions, thoughts, abilities, and orientations—to put something that matters to us into words. I then offered a formal analysis of the painting centered upon the compositional arrangement of the persimmons and their puzzling spatial distribution. Striking features include Muqi’s particularization of each of the persimmons (except for the two ‘ghostly’ ones on either end), his care to avoid occlusion and with it ready indications of the precise spatial relations between and among the fruits, and the astonishingly precise and eventful placement of the sepals on the forward persimmon (#3), a micro-stroke that induces a major re-orientation of the viewer’s implied position. In this post I’ll sketch some of the religious and intellectual background to the painting, and then try to get it into sharper focus with a comparison with Cézanne, a comparison guided by two of Rainer Maria Rilke’s characterization of the seeming metaphysical implications of Cézanne’s later works.

But first, what does it mean to say that the work is a Chan Buddhist painting? And why might we think that anything more than this bare identification of the work as Buddhist is relevant to understanding its seeming ineffability, or indeed anything of its meaning and significance? The standard account of the work goes something like this: Chan Buddhist painting exhibits a distinctive style that is expressive of its doctrine. The most distinctive feature of Chan Buddhism in relation to other kinds of Buddhism is its emphasis on the ‘suddenness’ of Enlightenment. The last words of the scroll of the central canonical statement of Chan, The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch Hui-neng, identify it in one of its earliest extant manuscripts as ‘Southern School Sudden Doctrine Platform Sutra of the Supreme Mahayana Vehicle, one roll’. This advocacy of suddenness is contrasted with an orientation towards ‘gradual’ Enlightenment that is attained through meritorious thoughts and actions. Chan painting, then, exemplifies Chan doctrine in its stylistic renunciation of mediating and elaborating elements in painting, such as virtuoso display of a variety of refined brushwork, any concern for gracefulness, reverence for past masters, or learned allusions. And it was Chan paintings’ stylistic bareness, its simplicity, and its cultivation of the sense of spontaneity that found no favor in China, but was prized in Japan.

As an instance of a text-book style classifactory schema of a text-book put to explanatory use, the standard story can scarcely be denied, but one notices that it tells us nothing about the distinctiveness of 6 Persimmons, nor does it intend to. To understand the distinctiveness of the artistic meaning of 6 Persimmons, we need to go further and ask how artworks might variously embody textual meanings. And this in turn requires some sense of how artworks embody any meanings, and of what kinds of meaningfulness are distinctive of textual meaning. The only philosophical account known to me that asks and proposes an answer to these questions with regard to textual meaning was given by the philosopher of art Richard Wollheim in the mid-1980s. Wollheim proposes the following schema: (i) with the aim of producing an artwork, an artist (Wollheim explicitly restricts his account to painting as an art; I see no reason not to expand it to include the arts generally) considers a range of existing works artworks (including perhaps her own) and notes that they are replete, in the sense that they embody an indefinite number of properties and an indefinite number of kinds of properties; (ii) in what Wollheim calls ‘reflexiveness’, the artist notices that there are previously unused or underexploited properties and/or kinds of properties that she might put to use in her own work in the service of creating a novel kind of ‘fit’ between perceptual properties and kinds of meaning; (iii) in what Wollheim calls ‘thematisation’ or ‘putting reflexiveness to work’ the artist the treats certain properties and/or kinds of properties as bearers of meaning and places them into relation with other such properties in an artwork in the service of creating or enhancing the meaning of the work; examples of thematisation include the High Renaissance’s use of facial expressions, the Venetian Cinquecento painters’ use of brushmarks, the use of edge and support in Degas, or the Cubists’ use of applied materials. Wollheim then argues that textual meaning in the arts enhances the conceptually more basic kinds of meaningfulness, representation and expression. Wollheim calls the latter kinds of meaning ‘primary’ meanings, and textuality as one of an indefinite class of ‘secondary’ meanings wherewith the artist expresses what the primary meanings mean to her.

Keeping in mind that our goal is ultimately to try to understand what it might mean to say that 6 Persimmons is ‘about’ ineffability, we now ask how Wollheim’s account might aid us in clarifying what sense Chan Buddhism might be part of the content of Muqi’s painting. In one sense it is easy to state the core conceptions of Chan Buddhism as a development of Mahāyāna Buddhism that emerged very roughly two thousand years ago. In another sense it is quite impossible to state the conceptions, both because they are of tremendous conceptual difficulty and subject to different manners of interpretation and understanding up to the present.

The best I can do here is to offer a short account based upon the founding document of Mahāyāna, a philosophical work of considerable greatness and even greater difficulty, Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamikakarika (interested readers are advised to consult the enormous secondary literature on it, starting perhaps with Paul Williams’s study of Buddhist thought, and Barry Allen’s book on Chinese epistemology for Chan specifically). As I (uncertainly) understand it, its core claims are stated in chapter 24. Nāgārjuna has asserted that all things are ‘empty’; this is standardly glossed as the assertion that all things lack ‘self-being’ or a subsistent nature or a substantive essence. The chapter opens with him presenting the objection that if all things are empty, then the Buddha’s teaching too is empty, and “it follows that/ The Four Noble Truths [i.e. all cyclic existence is suffering; suffering is caused by a craving resulting from ignorance; there is a release from suffering; the path to release is the eightfold Buddhist path of right view, right mindfulness, right action, etc.] do not exist” (XXIV:1) Nāgārjuna replies that this objection is based upon a misunderstanding of emptiness (XXIV:7), and crucially “Without a foundation in the conventional truth,/The significance of the ultimate cannot be taught./Without understanding the significance of the ultimate,/Liberation is not achieved” (XXIV:10). As Jay Garfield explicates this in his commentary, the key aspects of these claims are that part of “understanding the ultimate nature of things is just to understand that their conventional nature is merely conventional,” and that emptiness itself is to be explained and understood through the technical Buddhist doctrine of ‘dependent co-origination’, roughly that all things are impermanent, inter-dependent, and arise from (a web of) causes also so characterized. On some of Nāgārjuna’s formulations emptiness is dependent co-origination. Nothing in Chan Buddhist doctrine varies from these core formulations of Nāgārjuna; Chan gains its distinctiveness over against the alternative Buddhist claim that liberation is gradual, and in rejecting the doctrines of so-called Pure Land Buddhism that declare that after death a person of merit goes to an idyllic Western paradise. As Barry Allen puts it, “Chan is many things. It has roots in Mahayana Buddhism and the ideas of Nāgārjuna; it appropriates from the Daoist classics, as well as from earlier developments in Chinese Buddhism; and it is a Sinitic critique of Indocentrism, impatient with a Buddhism of translated sutras, imported relics, and foreign traditions” (Allen, p. 143).

So, still following Wollheim’s schema, we ask: what aspects, if any, of Mahāyāna Buddhism’s philosophy of so-called Madhyamika (the ‘middle way’ between thinking that substances, especially the soul, are eternal and that the soul is annihilated at death) generally, and Chan doctrine specifically, did Muqi render as the textual meaning of 6 Persimmons? To try to get this question into focus, I’ll make a comparison between the works of Muqi and those of Cézanne in the late phase of his final two decades. In letters to his wife in 1907, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke offered perhaps the first penetrating characterization of the nature of Cézanne’s achievement. Two of his remarks might be thought to apply equally to Muqi. (Here I follow the account in the art historian Kurt Badt’s canonical study, The Art of Cézanne, as translated into English by Sheila Ann Ogilvie; the translations in the standard volumes of Rilke’s selected letters, as well as those in the little volume published as Letters on Cézanne, markedly differ from each other, though hopefully not in ways that effect the points I’ll make). Badt quotes two of Rilke’s characterizations of the mysteriousness of things in Cézanne’s works, both of which might seem apt in characterizing Muqi’s: first, that the ‘mystery of things’ in Cézanne is their ‘perfect transcendence’, as Rilke wrote that these things ‘become so very objectively real, so simply indelible in their obstinate presence’” (p. 52); and that the purpose of Cézanne’s work was to induce ‘the process of making a thing “become” a thing, the reality which, by [Cézanne’s] own experience of an object, was intensified until it became indestructible’ (p. 58). Let’s set aside the last clause, as any talk of ‘experiences becoming indestructible’ is out of place in an account of Madhyamika or Chan ontology.

As Badt suggests, it’s easiest to see Cézanne’s procedures and artistic ideologies at work in his watercolors. Consider a minor and incomplete work, ‘Trees’ (1985) at the Barnes Foundation. What carries the sense of ‘obstinate presence’ and of a thing ‘becoming’ a thing? Typically Cézanne began with a light sketch of outlines, then began working from the darkest areas. A stark instance of this is the rendering of the largest and most prominent tree. The major work is in rendering the patches of shadow line the tree’s right edge. Badt, like other writers on Cézanne including Philip Rawson and Patrick Maynard, refer to this basic compositional technique as the creation of ‘shadow path’. This foundational use of the path carries two major senses. First, the path provides a basic order that does not respect the depicted contours of things. The shadowing combines what are both shadows on the objects and shadows cast by objects, and the line between the two is perceptually indiscernible. Further, the shadows will tend to link with other shadows, whether through contiguity or through separated rhyming or resonance. Second, the paths introduce a sense of the temporality of making with the perceptual distinction between relatively dark shadows and areas and relatively light ones. The chronology might be unrecoverable, but the sense of some temporality, some before-and-after is certain. Color is likewise applied sequentially, with blending largely avoided. Highlights are given through unworked areas; hence the overall subdued quality of the work, and one reason for the sense in Cézanne of an unusually close and intimate association of the nearest parts of the things and the material support.

Now Rilke’s remarks say nothing of the shadow paths, despite their centrality to Cézanne’s poetics, but perhaps we can explicate something of how they contribute to the formation of the sense of his objects’ ‘obstinate presence’ and of the exhibition of ‘things becoming things’ as follows: Cézanne’s use of shadow paths foregrounds the sense of the process of painting as temporal and constructive. Everything in the process seems to unfold so as to dramatize the sense of objects emerging from a broader, as it were trans-particular structuring force. The visibility of the individual marks and the quality of slow progressive build-up simultaneously self-dramatizes the act of making. What is made and what is seen are one, and each occurs through the other. As has been noted countless times, an effect of this is that the world of Cézanne’s paintings and drawings, the made-and-depicted world, seems to exclude the viewer. Cézanne’s world is other. This quality of otherness perhaps is part of what Rilke means by the objects’ ‘obstinate presence’: they seem to subsist through and beyond the limited act of viewing them. The sense of fused drama and self-dramatization likewise could plausibly be part of what Rilke meant with the sense of seeing things becoming things: an object is a product of broader forces, though locked in place by a web of compositional, inter-related forces.

Muqi’s six persimmons are shadowless, which together with the avoidance of occlusion analyzed in my previous post gives them their placelessness, largely unmoored quality even in relation to each other. One might apply Badt’s paraphrase of Rilke to them in one respect: they do seem to exhibit ‘perfect transcendence’ in the sense that they seem to be beyond all webs of physical causality and spatial placement. Muqi limits self-shadowing to the edges of the two ghost persimmons and the lower edge of the most forward piece of fruit, and in all three cases he permits the delimiting stroke to stand revealed, so as to subordinate shadow to brushstroke and translate and subsume the spatial implications of shadow into the determination of contour.

The comparison with Cézanne can now focus the question: What in Muqi’s piece is the compositional equivalent of Cézanne’s shadow paths? What holds the six persimmons together? Recalling Nāgārjuna’s claims, and Garfield’s explication of them as requiring the recognition of the conventional qua conventional, that is, the conventional in its very conventionality, one is led to the thought it is a convention, namely the classification of, and the habitual act of classifying, persimmons as persimmons that holds the fruits together. The function in Muqi of Cézanne’s procedures is carried not by seeing and shadow paths but by projecting and isolating.

I don’t doubt that this account seems to explicate the difficult with the irredeemably obscure. In my final blog post, I’ll try to clarify this sense of conventionality in Muqi and then show how it leads readily to the explication of the claim that 6 Persimmons is about ineffability.

References:

Barry Allen, Vanishing into Things (2015)

Kurt Badt, The Art of Cézanne (1956, translated by Sheila Ann Ogilvie (1965))

Hui-neng, The Platform Sutra (late 8th century, translated by Philip Yampolsky (1967))

Patrick Maynard, Drawing Distinctions (2005)

Nāgārjuna, Mūlamadhyamakākarikā (The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way), (1st-2nd century C.E. (translated with a commentary by Jay L. Garfield (1995))

Philip Rawson, Drawing (1969)

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters on Cézanne (1985, translated by Joel Agee)

-----Selected Letters 1902-1926 (1946, translated by R. F. C. Hull)

Paul Williams, Buddhist Thought (2000)

Richard Wollheim, ‘On the Question ‘Why Painting is an Art?’’, in Proceedings of the 8th International Wittgenstein Symposium (1984)

-----Painting as an Art (1987)