Now for my final post of the first draft of my book in the philosophy of meaning in the visual arts, I consider masks, a kind of visual art whose primary uses are in performance. Later drafts and the book will of course include accounts of the central visual art forms of drawing, painting, and sculpture; but since I am well past my initial goal of a 50,000 word draft, and because I have previously written and published many tens of thousands of words on those central art forms, I don’t think it necessary to include those central accounts in a first draft. Masks and masking do not admit of a short treatment, both because of the vast range of examples and the variety of their primary uses, and also because their primary uses are in performance—rituals, dances, mortuary practices, festivals, etc.—and so any account of the artistic meaning of a particular mask must include an account of its characteristic uses in the performance for which it was made and intended. I will not attempt here even the briefest survey of masking (for an outstanding such survey, see Gary Edson’s Masks and Masking: Faces of Tradition and Belief Worldwide (2005)), and will limit myself to summarizing the most penetrating account of masks in English, A. David Napier’s Masks, Transformation, and Paradox (1986), and then consider a few of the artistic uses of masks ‘at full stretch’, in particular in Nōh Theater and in the transformation masks of the Kwakwaka’wakw (formerly Kwakiutl).

The ur-act of masking is (a) the creation of a rigid artifact (a mask) marked with one or more of the canonical features of the human face (eyes, nose, mouth) and (b) placement and securing of the mask onto the head so as to obscure the face of the person wearing it. Typically, though far from universally, the mask is painted and/or decorated non-naturalistically, that is, in ways that do not imitate the color and tone of the face, but rather with patches of bright color that provide striking contrasts and instant recognizability from a considerable distance and/or when the mask moves in ritual, dramatic performance, or dance. The mask is further typically identifiable as some known type—a member of a social class or of a particular social group, an animal, or a special being such as a particular god, demon, or witch. The rigidity of the mask affords a steady contrast with the characteristic expressive mobility of the canonical human face it obscures. So the ur-act of masking, with the performative use of the mask, carries immediately the quality of Ellen Dissanayake’s ‘making-special’ discussed earlier in the book as part of the proto-behavior of the arts generally. As Johannes Huizinga put it in Homo Ludens, “The sight of the masked figure, as a purely aesthetic experience, carries us beyond “ordinary life” into a world where something other than daylight reigns; it carries us back to the world of the savage, the child and the poet, which is the world of play . . .” (quoted in Edson, p. 5) Because the mask obscures the face of its wearer and offers another extra-ordinary identity, the mask in use immediately induces a sense of transformation, from ordinary being to extra-ordinary, with the further possibility of changing masks so as to enact and exhibit the transformation of one special being into another. In the transformation A B (e.g. person to masked being) the question of reality attaches to both items: Is the A really (already) a B? Is the transformation ‘real’ or merely apparent, temporary or permanent? Is B what is really real, and A a mere appearance? Is A what is really real from one point of view, and B from another point of view? And so forth. Napier summarizes this fundamental semantic dimension of masking with the thought that masking carries “a metaphysics of ambivalence” (Napier, p. xxv) that includes also the categories of change, appearance, and ambiguity. Mircea Eliade had long ago noticed that masking cultures are overwhelming polytheistic, whereas in the great monotheisms masking is usually an abomination or at least non-serious, as monotheists usually consider the identity of a person fixed by birth, and so the sorts of identity-shifting transformations induced in masking can play no ontological role. By contrast, as Napier notes, there is an elective affinity between masking and polytheism, as the latter has a constitutive plurality, and so potentially conflicting, of sources of authority; with multiple gods “the pantheon has institutionalized uncertainty itself in recognizing more than one possible standard” (p. 25). Further, anthropologists have noted that masking is particularly prominent in totemistic societies, as the animal mask provides an evidently appropriate means of expressing relations among humans and their totem animals.

Is masking then a visual art form in the sense I have introduced and explicated here? I somewhat reluctantly conclude that, because of the constitutively performative nature of masking (note characteristic (b) in the fundamental characterization of the ur-act of masks), the answer is no, and that masks are more rightly and illuminatingly treated as a part of the visual staging of performative arts (I hope to treat the performative arts at length in the fourth volume of my series on the philosophy of meaning in the arts, with the second and third volumes addressing contemporary art and poetry respectively). Let us consider a great historical range of examples of masking. There are a number of paleolithic figures, both cave paintings and sculptures, which display human bodies and animal heads. It is not possible to determine whether these are theriomorphs proper—composite beings, whether transformed humans or divine figures—or masked humans. The earliest known masks are those from approximately 11,000 BCE found in Israel/Palestine.

The circumstances of the use of these masks are necessarily conjectural, though an exceptionally interesting and imaginative proposal comes from the art historian Hans Belting, who begins from the thought that there survive in that region from a somewhat later period fragile plaster humanoid statues and plastered human skulls with cowries for eyes.

There is an attested practice of removing the skulls of the dead and burying them. Anthropological parallels suggest that these were the skulls of particularly important people whose continued presence after death was ritually maintained. So during a period of the skull’s de-fleshing burial, substitutes in the form of statues were displayed, which were then ritually buried with the installment of the de-fleshed and plastered skulls. Masks then might have played some role of impersonating the dead in ritual performances. The uncertainty of the interpretation matches the paucity of the evidence, but the interpretation is at least plausible and loosely supported by the vast anthropological evidence of masks in mortuary practices and rituals. As Belting notes, “[i]n the cult of the dead, images were at first accessories to performances—masks, makeup, costumes, and disguises” (Belting, p. 89) whose fundamental significance he describes very much in the terms used by Napier: “The mask was an epochal invention and one that gives the paradox of the image—its making visible an absence—its most definitive expression. . . with its single surface, the mask accomplishes both concealment and exposure, like the image, it draws its vitality from an absence, which it replaces with a substitute presence . . . The image, by placing the final seal on the real body, becomes the medium of its new presence, a presence that time and mortality cannot touch.” (p. 93)

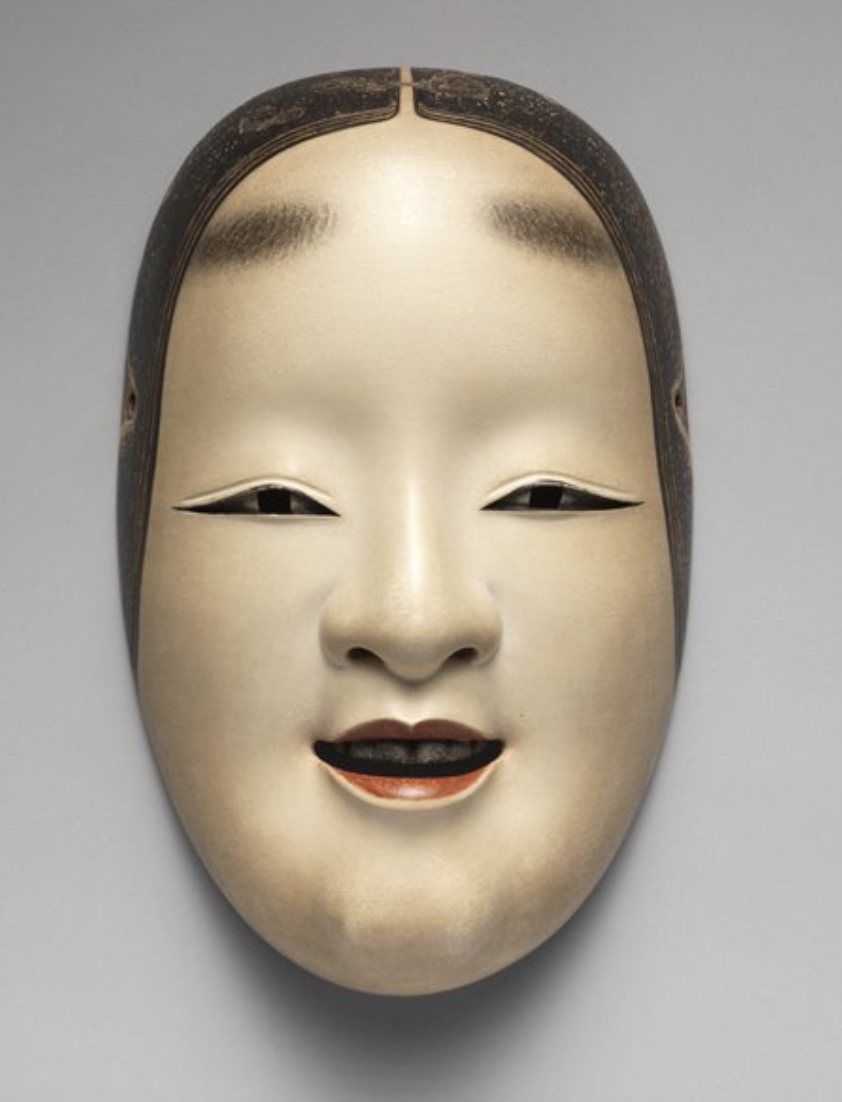

Masks are prominent in the world’s theatrical traditions, and are especially valued in the Japanese Nōh theater, which continues to the present and which was given a set of authoritative guidelines, strictures, and aims in the treatises of its great founding figure Zeami in the late 14th-early 15th centuries. In her book on masking in Nōh and Balinese masked dance-drama, Margaret Coldiron treats the mask in performance as a tangible, embodied expression of a spiritual power inherent in artistic creation.

On the specific metaphoricity of the mask in performance she quotes Mark Nearman on the shifting sense of the Japanese ideogram for ‘mask’: “In Zeami’s time, it was read men, as an abbreviation of kamen, ‘substitute or provisional face’. This character was now read omote in Nô circles to emphasise the notion that the object represented an actual face and was to be treated as such by the actor.” (Nearman, p. 43, quoted in Coldiron, p. 143) The prototypical artistic uses of the mask involve the actor’s tilting of the head, as explicated by Eric Rath: “An actor’s use of a mask can suggest psychological nuances to a role. By tilting the mask slightly upward, “brightening” it, the actor allows more light to strike the mask’s features, making the mask appear to laugh or smile. Tilting the mask downward “clouds” it, causing the mask to appear to cry or brood. The ambivalence of the mask’s features at such moments hint at a range of emotions left to the members of the audience to decipher.” (Rath, p. 13)

Similarly, the artistic uses of the Kwakwaka’wakw transformation masks in performance (and so as part of performative arts, not primarily the visual arts as explored in this book) gain their power and significance as props used in enacting mythic tales and transformation; as Audrey Hawthorn puts it in the standard study Kwakiutl Art, “[c]arefully carved and balanced on hinges, the mask was intricately strung. At the climatic [sic] moment of the dance, the dancing, the music, and the beat of the batons all changed tempo, speeding up just before the transformation and then halting while it occurred. When certain strings were pulled by the dance, the external shell of the mask split, usually into four sections, sometimes into two. These pieces of the external covering continued to separate until the inner character was revealed, suspended in their center.” (Hawthorn, p. 238) In many cases what was revealed in the transformation was the mask of a human face, perhaps representing a totemic ancestor, behind a totem animal’s head, as in this eagle-man transformation mask:

Examples of such performative masking could be easily multiplied by considering the great masking traditions of West Africa, or the artistic tradition of Ancient Greek tragedy. One simple summarizing point would be that with regard to artworks and their art forms, and perhaps with artifacts generally, their meaning cannot be explicated, nor their classifications secured, without considering their characteristic uses. With this modest thought I conclude the first draft of the book, the second draft of which shall surely continue with the consideration of the paradigmatic visual arts of drawing, painting, and sculpture.

References and Works Consulted:

Hans Belting, An Anthropology of Images: Picture, Medium, Body (2014)

Margaret Coldiron, Trance and Transformation of the Actor in Japanese Noh and Balinese Masked Dance-Drama (2004)

Ellen Dissanayake, Homo Aestheticus (1992)

Gary Edson, Masks and Masking: Faces of Tradition and Belief Worldwide (2005)

Judith E. Filitz, ‘Of Masks and Men: Thoughts on Masks from Different Perspectives’, in The Physicality of the Other: Masks from the ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean (2018), ed. Berlejung and Filitz

Audrey Hawthorn, Kwakiutl Art (1988)

Huizinga, Homo Ludens (1938)

A. David Napier, Masks, Transformation, and Paradox (1986)

Mark Nearman, ‘Behind the Mask of Nô’, in Nô/Kyôgen Masks and Performance (1984), ed. Rebecca Teele

Eric C. Rath, The Ethos of Noh Actors and Their Art (2004)

Zeami, On the Art of Nō Drama: the Major Treatises of Zeami (1984)