In my recent work in the philosophy of art one of my major concerns has been to provide an account of the varieties of artistic meaning, particularly those that are prominent in the visual arts. My major model of such an account is the conceptual scheme set out by Richard Wollheim in his Painting as an Art. Wollheim claims that an artist paints so as “to produce content or meaning”, and further in such a way as to produce a pleasurable experience for a viewer (Wollheim (1987), p. 44). The book analyzes a variety of kinds of artistic meaning, first of all representation and expression at considerable length, and also metaphor, historical meaning (where the artist makes the painting’s historical character part of its content), and textual meaning (where the artist makes some bit of text, say, a philosophical claim or an ideological statement, part of its content), and Wollheim left open what if any further kinds of artistic meaning occur in painting. In his recently published lectures from a manuscript left unfinished at his death Wollheim gave an analysis of the concept of organization in artistic pictures. In two recent posts I gave an account of Wollheim’s novel conception of pictorial organization, and asked whether one might reasonably take organization to be a further kind of artistic meaning. I suggested that it should be so credited, as organization plainly contributes massively to the total meaning of an artwork, but I also noted a tension between treating pictorial organization as a kind of meaning, and Wollheim’s explicit though theoretically unstressed equation of meaning with content. One wonders: is content not what organization organizes? In light of this and other problems that arise in treating artistic meaning as content, I have preferred to treat Michael Podro’s conception of artistic meaning as ‘sustaining recognition’ (see Podro (1999) and the relevant sections of my manuscript posted on my blog in the past year or so).

Here I’ll propose a conception of a further kind of artistic meaning that I call ‘resonance’. The thought that resonance is a kind of artistic meaning first occurred to me in thinking about the peculiar power of the artist Gema Alava’s piece ‘Trust Me’, a performative work wherein Alava leads someone blindfolded, typically a member of the artworld such as an artist or critic through a museum exhibition and describes the works therein.

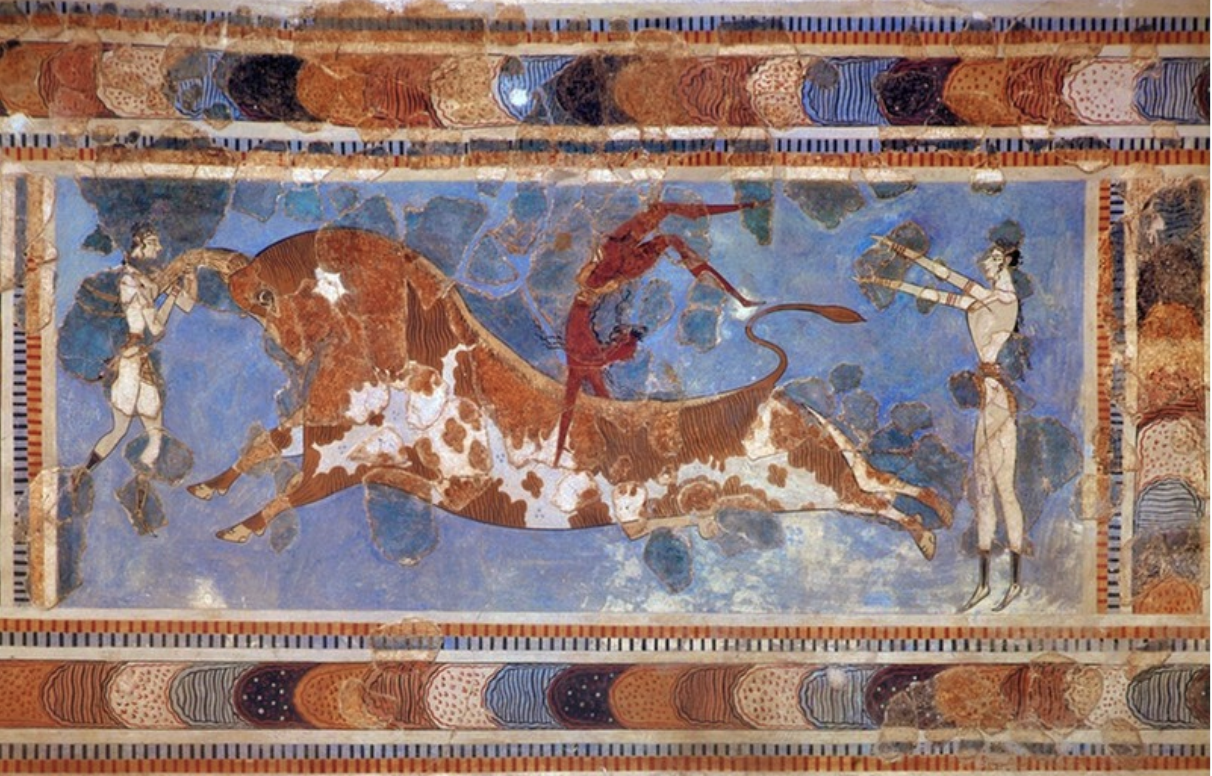

In some obscure way that piece seemed to call up my earliest experiences in the visual arts, as I had by the age of 10 acquired a copy of the so-called ‘Bull Leaping’ fresco at the Minoan palace in Knossos,

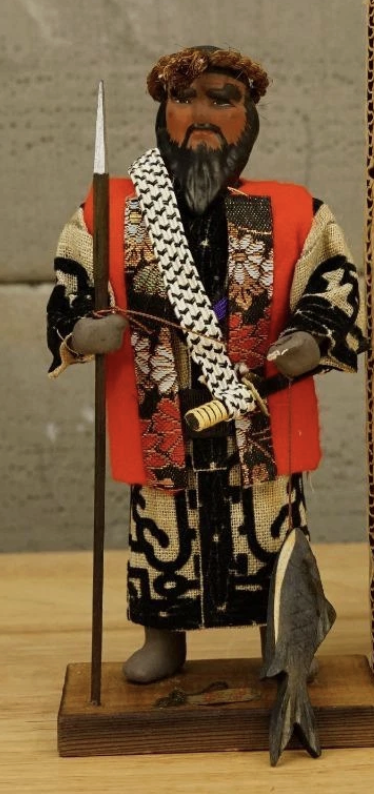

and a small statue of a man bought in Japan at an Ainu village near Asahikawa.

Likewise evoked was David Lewis-Williams’s remark about preparing to visit the Paleolithic paintings in the cave at Lascaux. Since the closure of the cave to the public in 1963 researchers are allowed only twenty-minute visits. Lewis-Williams asked a researcher what he had been able to see in the twenty midnights, and he replied ‘Nothing’. Lewis-Williams asked why, and the researcher replied ‘because I was crying the whole time’. My suggestion is that at least part of the intensity of response to these artworks arises from the recognition of the resonance they embody and evoke.

What then is resonance as a kind of artistic meaning? I follow Wollheim’s methodology as exhibited in Painting as an Art by starting with the thought that an account of a kind of artistic meaning has two major aspects: the identification of human species-wide capacities and associated phenomena in ordinary, non-artistic contexts; and then the exhibition of the ways in which artists recruited these phenomena in artworks in the service of making their works richly meaningful. In order to help locate the relevant non-artistic phenomena, I’ll start with a characterization of artistic resonance: Artistic resonance is (a) a kind of artistic meaning wherein (b) the ‘invitation to participate’ that is partly constitutive of artworks is (c) ‘thematized’ (again in the sense analyzed by Wollheim) so as to become part of the total meaning of the artwork. I’ll return to the explication of the key (and philosophically novel) characteristic (b) after first laying out the relevant non-artistic basis. In their recent book The Politics of Language, David Beaver and Jason Stanley have spoken of a recent ‘resonance zeitgeist’ wherein scholars across academic fields in the humanities and social sciences have introduced the concept of resonance (Beaver and Stanley, pp. 32-8) in the service of explaining some phenomena targeted by their research. So in the sociology of message framing, the researcher seeks to understand why one way of framing some political message fails to induce political activism, while another way ‘resonates’ in the sense that people find themselves moved and energized and so induced to become politically active (pp. 33-6). In the study of rituals chants are said to be “sources of harmony . . . and are similar to vibrating tuning forks that beg others to join them in resonance (p. 36, quoting Robert St. Clair (1999), p. 80). Beavers and Stanley themselves consider resonance to be a linguistic phenomenon, and in their book-length account they treat resonance as part of a conceptual complex together with ‘attunement’ and ‘harmony’; very briefly, they argue that resonance-attunement-harmony is a sociolinguistic phenomenon that is basic to all language use, one that arises from the fact that language is always a social phenomenon and, as with human action generally, what is meant in any instance is always much more than what explicitly signaled (p. 62). Human beings, in the course of their socialization and everyday interactions, ‘attune’ themselves to the presuppositions and implications of their fellows’ actions and speech (p. 80), and under the shifting circumstances of human life come to ‘harmonize’ themselves with their social environments (p. 119).

There is a great deal to be learned from Beavers’s and Stanley’s important book, but the relevant non-artistic conception of resonance is given, I think, in the most prominent of academic writings of the sociologist and social theorist Hartmut Rosa in his big book Resonance (briefly discussed by Beavers and Stanley (pp. 36-7), an account which is summarized and elaborated in two short more recent books, Democracy Needs Religion and Time and World. For Rosa the concept of resonance has both descriptive and normative employments. In its descriptive use it is part of philosophical anthropology and of what Rosa calls a ‘relational ontology’ that takes its inspiration from the philosopher Charles Taylor, and it characterizes basic situations wherein human beings experience themselves as (i) affected by something (whether natural, organic, or human) (ii) to which they form a connection, and (iii) and in light of which they experience themselves as transformed into a new state. The most general characteristic of resonance i-iii is (iv) its unpredictability for initial orientation to Rosa’s conception, see his most succinct formulation in Rosa (2024), pp. 45-53). In its normative employment resonance is counterposed to alienation as the two great kinds of human beings’ relation to their worlds. In resonant relations the world (again in the broadest and most capacious sense) the world is experienced as responsive yet uncontrolled by the person to whom it is related, and as if ‘having a voice’; by contrast in alienated relations the world is unresponsive, controlled or dominated, and mute. I treat both of Rosa’s uses, that is, resonance both in its descriptive sense and its normative sense, as providing the pre-artistic background, available to all human beings and so something artists’ can rely upon as part of their audience’s cognitive and emotional resources, out of which artist’s draw artistic resonance.

Again, following Wollheim, I’ll consider artistic resonance as a kind of artistic meaning wherein the artist thematizes some basic and initially inert feature of the artwork as it emerges in the process of artistic creation. The two basic features, I suggest, are the constitutive character of what Ellen Dissanayake has called ‘making special’ (which in recent years she calls ‘artifying’), and the element of the artwork that the English art writer Adrian Stokes has called the ‘incantatory’ character of artworks. Making special/artifying involves the artist “embellishing, exaggerating, patterning, juxtaposing, shaping, and transforming” utilitarian and ordinary materials and artifacts so as to draw attention to them and make them expressive and memorable (Dissanayake, p. 53). With regard to the incantatory aspect of artworks, Stokes writes that “in every instance of art we receive a persuasive invitation . . . to participate more closely. . . the learned response to that invitation is the aesthetic way of looking at an object.” (Stokes, p. 269) In the incantatory aspect the audience tends to experience itself as enveloped by the work of art, to experience itself as transformed by it, and as if identified with it. The incantatory aspect is a structural feature of all artworks, though one that is particularly evident in “dance, song, rhythm, alliteration, rhyme, [which] lend themselves to, or create, an incantatory process, a unitary involvement, an elation if you will.” (p. 272) Stokes goes on to add that there is another dimension of artworks wherein we do not identify with the work, but experience it as something set over against ourselves. Putting this together with the incantatory aspect gives something close to Rosa’s conception of resonance as transformative and voiced.

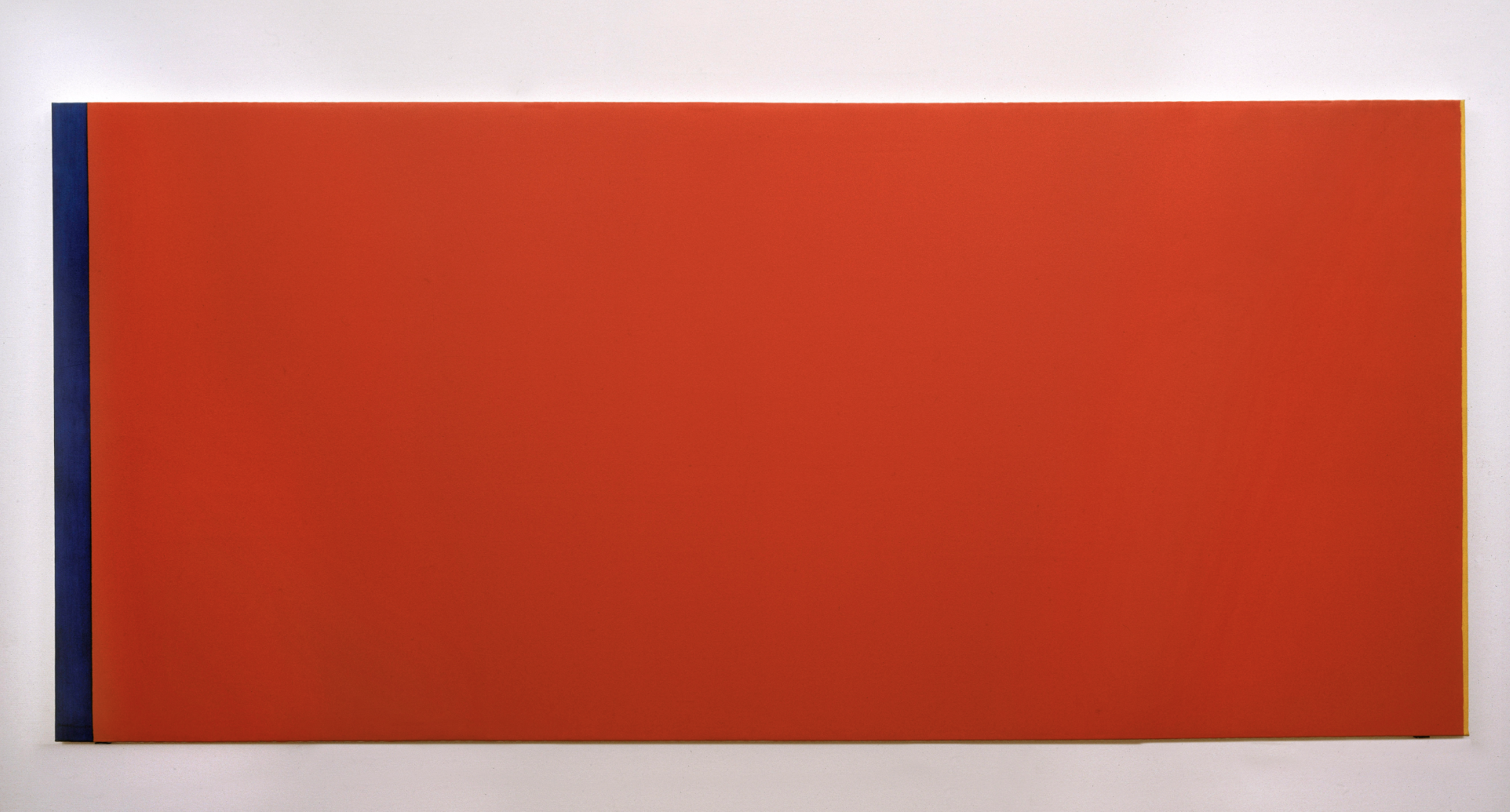

The reader will notice that on this account artistic resonance does not seem to be so much a distinctive kind of artistic meaning, but rather just a way of stating the peculiar attractiveness of artworks generally. This does not seem to me to be an objection: just as some of Wollheim’s kinds of artistic meaning--representation, expression, metaphor--might be thought to be parts of the meaning of all artworks, so artistic resonance seems a kind of feature of artworks generally, but one which is put to use by the artist to create and enrich her works with further meaning. On the Wollheimian schema, artistic resonance qua kind of artistic meaning thematizes artistic resonance as a constitutive feature of artworks. With artistic resonance, the artwork itself takes on an enchanted and ‘voiced’ quality. To see how this works, one needs to consider a wide range of cases across the arts, which is part of my multi-volume project, and of which I have given an initial instance in the analysis of Alava’s piece in my book Retorno de la Obscuridad. A further benefit of treating resonance as a distinctive kind of artistic meaning that was not recognized by Wollheim is that it provides an appealing alternative account to a range of artworks that Wollheim himself struggled with. For example, in his famous early lecture ‘Minimal Art’, Wollheim treated Duchamp’s urinal as a piece that isolated the terminal moment of the artistic process, that is, the moment when the artist says ‘This is finished’, and presented that moment, and nothing but that moment. One problem with that account is that does not seem to provide materials for explaining why Duchamp’s piece has seemed so ‘fertile’, that is, why it has provided orientation for novel kinds of art-making. Similarly, in Wollheim’s graduate lectures at UC Berkeley that I attended in the Fall of 1986, Wollheim declared that Barnett Newman’s paintings were not examples of artistic painting at all, because they failed to exercise the perceptual capacities (in particular what he called ‘seeing-in’) whose employment was the pre-condition for paintings to acquire meaning at all.

But if one were to treat these problematic instances instead as novel ways of inducing the sense of artistic resonance, one could have a least a handhold for explicating the distinctive artistic power of these works. I’ll try to treat these works in this manner in a re-written and greatly expanded English version of my book.

I do not expect anyone to find this sketch of artistic resonance convincing as it stands, but hopefully the filled-out account in my upcoming book on the philosophy of artistic meaning will be more convincing, and that this sketch will at least prove stimulating.

References and Works Consulted:

David Beaver and Jason Stanley, The Politics of Language (2025)

Ellen Dissanayake, Homo Aestheticus (1992) [made special as presupposition of address/noticing]

--Art and Intimacy (2012)

David Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art (2002)

Terence McDonnell, Christopher Bail, and Iddo Tavory, ‘A Theory of Resonance’, in Sociological Theory (2017)

Michael Podro, Depiction (1999)

John Rapko, Retorno a la Oscuridad (2023)

Hartmut Rosa, Resonance (2019)

--Democracy Needs Religion (2024)

--Time and World (2025)

Robert St. Clair, ‘Cultural Wisdom, Communication Theory, and the Metaphor of Resonance’, in Intercultural Communication Studies 8 (1999)

Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self (1989) and A Secular Age (2007)

Adrian Stokes, The Invitation in Art (1965), in The Collected Books of Adrian Stokes, Volume 3 (1978)

Richard Wollheim, ‘Minimal Art’, in On Art and the Mind (1973)