The aim of the following book is to give a philosophical account of artistic meaning. Such an account is largely analytical in the sense that it cites instances artistic meaningfulness and states what they are, how they arise, and what characteristic effects they have. But such a philosophical account, as I understand it, also has reconstructive, stipulative, and even polemical aspects. These further aspects stem from the controversial nature and characteristics of artistic meaning-- controversial, that is, in light of prominent kinds of attitudes in modern and recent philosophical thinking towards the phenomena and issues invoked in the terms ‘artistic’ and ‘meaning’. Any philosophical discussion of the term ‘artistic’ brings in train at the very least a history of over two hundred years of thinking about what if anything is distinctive of artworks as opposed on the one hand to beautiful natural objects and phenomena, and other the other everyday and/or non-artistic artifacts. This philosophical thinking circles around a small number of questions: Are there necessary and sufficient conditions for something being a work of art, or is arthood exhibited by artifacts that exhibit some large part of a distinctive profile of characteristics? Is the term ‘art’ only strictly appropriate for modern artifacts produced with the aim of being experienced in special settings, or does the term also include at least some of the products of modern industries that aim for mass consumption? Or is it rather that the term ‘art’ names a human universal? Or to the contrary, does the term ‘art’ pick out nothing in human life, in that it is only used as a way for Western elites to ratify their own tastes and aversions? In marked contrast the term ‘artistic meaning’ is little discussed in philosophy. Many accounts of the concept of art include consideration of the value of art generally as well as the kinds of particular values that are characteristic of especially successful artworks. To so much as get the phenomenon of meaning into focus requires a great deal of effort, if for no other reason than, as I once heard the philosopher Hans Sluga say, the word ‘meaning’ means many things. I take it that most people who think that there is a class of artifacts rightly called ‘artistic’ would agree that among those artifacts are Bach’s Goldberg Variations, William Blake’s ‘Auguries of Innocence’, and Pablo Picasso’s ‘Three Dancers’, but there is no consensus on what those works ‘mean’, and if they do bear some meaning (s) whether such are rightly referred to as distinctively artistic. A further problem arises from the predominance of what one might call the linguistic conceptions of meaning: meaning is something uniquely expressed in language and consists in what a term refers to, or what a sentence states. If there is such a phenomenon as artistic meaning of, say, the Goldberg Variations, no one would think that it could be stated in a finite series of sentences. Can there be a philosophical account of something so controversial and/or obscure?

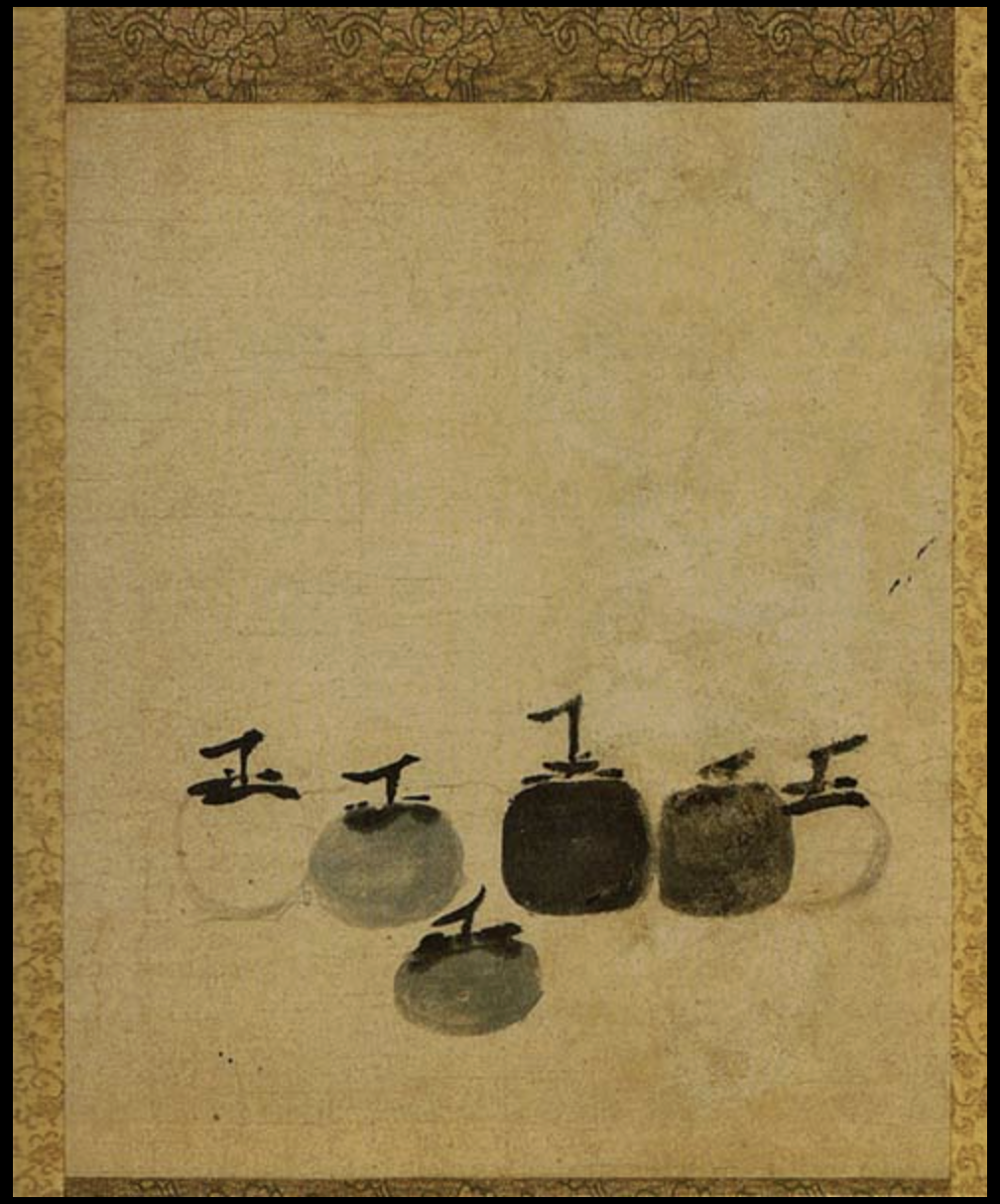

This book starts with the claim, or better the assumption, that the world’s artworks--the indeterminately vast number of artistic paintings, songs, plays, and also pots, blankets, and shields--possess artistic meanings to varying degrees and in countless complex ways. I do not think that there is any short argument, and probably not any long argument, for this assumption. I treat this assumption as a piece of philosophical anthropology in the sense that it arises from survey of and reflection upon the characteristic phenomena of human life--the life-cycle, the nature of human embodiment, perception, imagination, and cognition, the common nature and infinite cultural varieties of human beings, and their education and socialization into practices and institutions--together with the reflective attempt to understand these. After introducing a few typical artworks--a painting,

a poem,

a dance

--I ask the first guiding question: How are such artifacts so much as generally intelligible, that is, how is it that they can be experienced, enjoyed, understood, and appreciated outside of their initial audience? The very framing of the question of course controversially presupposes that such artifacts can be and are understood outside their proximal audience. I shall try to explicate how the general intelligibility of artworks arises from the ways that their artistic meanings, and the artworks’ making, presentation, and reception, necessarily draw upon general features of human sensibility, what once and could still be called a common human nature. I investigate five such classes of features, those involved human embodiment or corporeality, gesture, perception, tool-making and the making and use of artifacts, and language, and so call these the five great reservoirs of artistic meaning. I then investigate the mechanisms through which human beings draw from these reservoirs in the creation of artistic meanings. The basic form of such mechanisms is most readily seen in metaphor, which involves projecting some kind of frame or content that is treated as relatively well understood or intelligible onto something that is relatively poorly understood or intelligible.

Finally I consider the great classes of kinds of artistic meaning. The first three, representation, expression, and metaphor proper, have been much discussed in philosophy and so I very largely just draw upon existing accounts. I’ll also treat a relatively little explored concept, that of resonance, which I take to be what is involved in the universal address of artworks to perceive and participate in them, among the kinds of artistic meaningfulness; on that point the book, lacking philosophical precedents, will be forced to originality. I’ll conclude by returning to the instances of artworks introduced at the beginning in order to show that one use to which the account of artistic meaning may be put is to increase and intensify our understanding of actually existing artworks.

In providing an initial and partially stipulative general account of artistic meaning, the book is meant to provide a foundation for a further series of books treating specific kinds of art, in particular visual art, contemporary art, the performative arts of theater and dance, and poetry.