In my previous post I gave in barest outline a summary of the just-published materials presenting Richard Wollheim’s conception of pictorial organization in artistic painting. Again, Wollheim argues that pictorial organization comes in three ‘grades’, that arising from painters’ attempts to include whatever they wish the painting to show; that arising from an interest in ‘good’ organization and that instantiates values internal to organization such as order, balance, and symmetry; and that arising from “when the painter successfully arranges his painting so as to advance some further end: that is to say, some end the understanding of which does not require us to refer back to the nature of organization itself” (Wollheim (2025), p. 62). In the analyses he provides he is particularly concerned to show that the third and highest grade of organization conflicts in important cases with the second grade (Jacob van Ruisdael and Monet), and also how the third grade occurs when the painter respects the the second grade (Poussin). Now, Wollheim’s conception of pictorial organization is not free-standing, but unsurprisingly presupposes for its intelligibility his more general views on artistic meaning in painting. Here I’ll try to sketch those conceptually more basic views, as well as provide some art-historical background, or what I strongly suspect is part of the art-historical material that inspired Wollheim, namely, the art historian Meyer Schapiro’s theoretical account of coherence in art and his famous analyses of artistic organization in the Romanesque relief sculptures at Souillac and Moissac.

1. In the past year I posted partial accounts of Wollheim’s conception of artistic meaning as part of my first draft of a book on the philosophy of the visual arts, although there I adopted an approach more inspired by the philosopher Michael Podro. Wollheim’s fullest statement of his views is of course in Painting as an Art (1987), based upon his Mellon Lectures of 1984. As presented there, Wollheim’s conception of artistic meaning comprises three claims: (a) Meaning in painting is psychological (and not linguistic), and the meaning of a painting “rests upon the experience induced in an adequately sensitive, adequately informed, spectator by looking at the surface of the painting as the intentions of the artist led him to mark it” (p. 22); (b) Artistic meaning arises from a process that Wollheim calls ‘thematization’, wherein the artist “abstracts some hitherto unconsidered, hence unintentional, aspect of what he is doing or what he is working on, and makes the thought of this feature contribute to guiding his future activity” (p. 20), and primary instances of what is initially unconsidered in the process of painting are marks, surfaces, edges, and images, and the end towards which the process of thematization ends is “the acquisition of content or meaning” (p. 22); There are two broad and indeterminately large classes of artistic meaning, both of which derive from the creative process whereby the work is made. Primary meaning consists of familiar kinds of artistic meaningfulness such as representation and expression, and also such mechanisms as metaphor, textual meaning introduced through invocations of linguistic meaning, and historical meaning introduced through invocations of historically prior artworks. Secondary meaning is a difficult conception that Wollheim characterizes as a special kind of meaning which does not as it were directly contribute to the meaning of the whole artworks, but which rather proximally manifests or expresses what the primary meaning means to the artist (Wollheim’s major attempt to illustrate secondary meaning is a chapter largely on Ingres that is beyond my abilities to present both in summary and as plausible). In a slightly later essay on Nelson Goodman’s account of artistic meaning, Wollheim asserts that artistic meaning is not ‘teleological’, that is, it is not restricted to whatever is involved in the artwork that facilitates the work’s use to fulfill some non-artistic (such as religious or political) aim; but rather artistic meaning is semantic, and that artistic meaning follows four principles: (i) the Principle of Integrity, “that each work of art has its one and only meaning; (ii) the Principle of Intentionalism, “that meaning derives from the fulfilled intentions of the artist; (iii) the Principle of Experience, “that the intentions of the artist are fulfilled in the appropriate experiences of the spectator”; and (iv) the Principle of Historicity, “that all works of art possess intrinsically a history of production” (Wollheim (2025), pp. 304-06).

How might we understand Wollheim’s account of pictorial organization within his basic conception of artistic meaning? On the one hand, his discussions and analyses of art say very little about pictorial organization, which seems a striking lacuna in a philosophy oriented towards understanding the distinctive kinds of non-‘teleological’ and distinctively artistic meaning. On the face of it one could simply include pictorial organization among the kinds of primary meaning, and indeed Wollheim did say that his discussion of primary meaning in Painting as an Art did not aim at an exhaustive account. And one might imagine aspects of pictorial organization in a given artwork as being put to use in creating secondary meaning. On the other hand, treating pictorial organization as a kind of primary artistic meaning seems to violate Wollheim’s later stricture that artistic meaning is semantic, if one treats semantic meaning as something that admits of expression in the statements and propositions of language. My inclination is to bypass the issue as superficial, because the claim that artistic meaning is semantic in the later essay is only meant to mark it off as something distinct from the teleological.

2. Meyer Schapiro as a (Likely) Major Source of Wollheim’s Conception of Pictorial Organization:

At several points in his writings Wollheim expressed admiration for the work of the art historian Meyer Schapiro, in particular for his essay ‘On Perfection, Coherence, and Unity of Form and Content’ of 1966. One senses an atmosphere of Schapiro’s essay throughout Wollheim’s discussion of pictorial organization. In that essay Schapiro reflects upon typical terms of praise of works of art: that they are perfect, that they form and exhibit a coherence of the various heterogeneous elements that comprise them, that they exhibit an admirable unity of form and content. Schapiro begins by noting two features of such judgments of quality: first, that “[t]hey are never fully confirmed, but are sometimes invalidated by a single new observation”; second, that “there are great works in which these qualities are lacking” (Schapiro (1994), p. 33).

The first feature indicates that the nature of such judgments of quality is and can only ever be a hypothesis (pp. 37 and 42), and is so because the perception of a work of art is always incomplete: “in an object as complex as a novel, a building, a picture, a sonata, our impression of the whole is a resultant or summation . . . [but] We cannot hold in view more than a few parts or aspects, as we are directed by a past experience, an expectation and habit of seeing, which is highly selective even in close scrutiny of an object intended for the fullest, most attentive perception.” (p. 37) So “[t]o see the work as it is one must be able to shift one’s attitude in passing from part to part, from one aspect to another, and to enrich the whole progressively in successive perceptions.” (p. 48) Once one registers the necessarily hypothetical character of central judgments of quality in art stemming from the unavoidable incompleteness of perception of works of art and their multi-faceted and multi-dimensional character, ‘critical seeing’, which Schapiro seems also to characterize as the kind of scrutiny “intended for the fullest, most attentive perception” (p. 37), accordingly “is explorative and dwells on details as well as on the large aspects that we call the whole”. The love of detail is everywhere exhibited in Wollheim’s accounts of particular pictures, not just in the lectures on pictorial organization but also throughout the accounts of paintings in Painting as an Art and even in his critical writings on recent art figures such as Nicolas de Staël, Frank Auerbach, Wayne Thiebaud, and Tim Rollins and K.O.S. (all hopefully available soon in the forthcoming NYRB collection of Wollheim’s art criticism edited by his son Bruno Wollheim). And one notices how in every case when Wollheim discusses the highest grade of pictorial organization in Jacob van Ruisdael he dwells on the ways in which the painter provides details in order compensate for and induce reflection upon the great asymmetries of Ruisdael’s works.

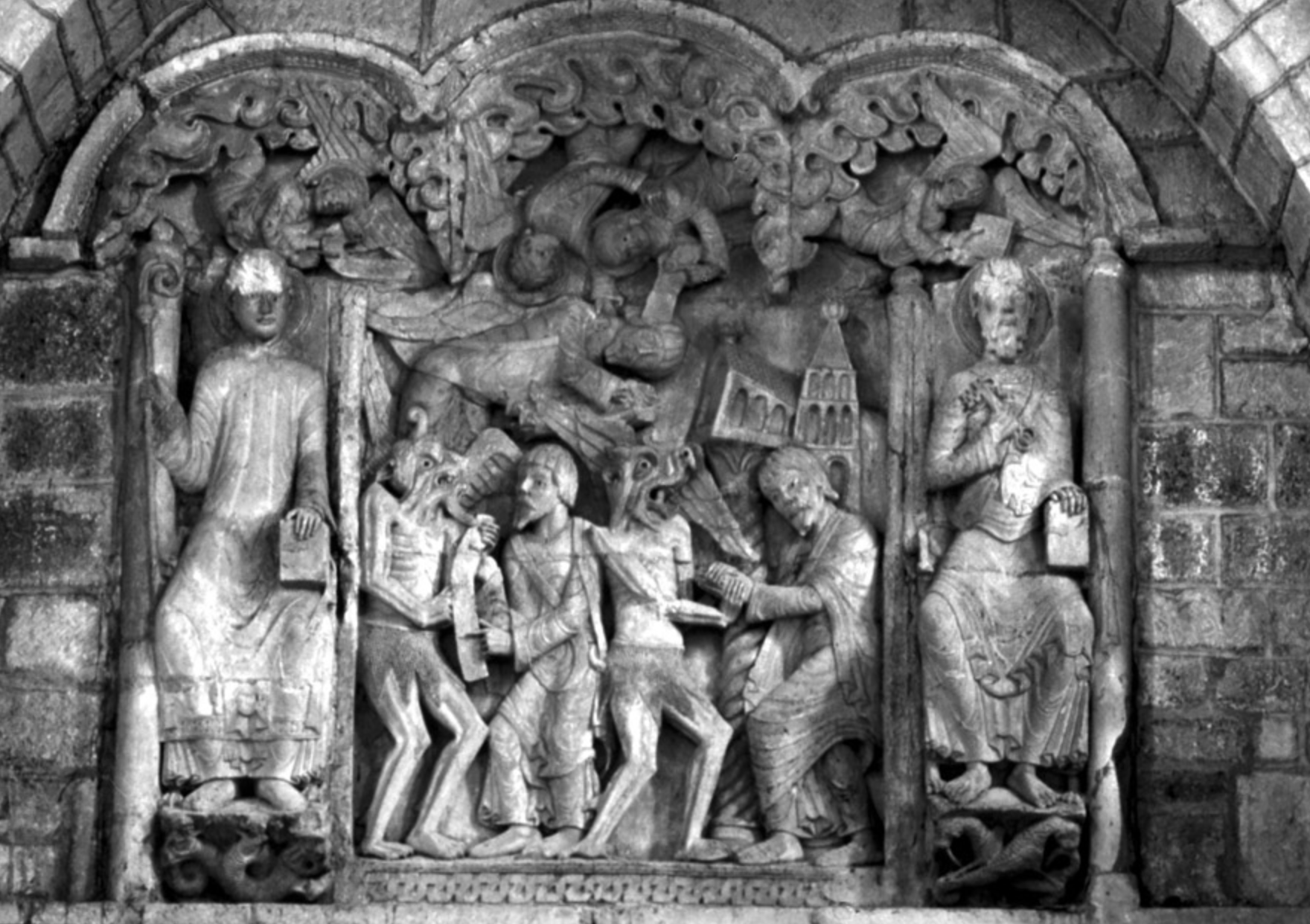

With regard to the second feature of judgments of quality, that qualities such as perfection and coherence are not indispensable in great works of art, Schapiro notes with regard to Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling that “one might entertain the thought that in the greatest works of all such incompleteness and inconsistency [in the scale of the figures] are evidences of the living process of the most serious and daring art which is rarely realized fully according to a fixed plan, but undergoes the contingencies of a prolonged effort” (pp. 35-7). Referring to his own famous analyses of the Romanesque relief at Souillac, notes how the work was long judged by observers to be incomplete because it seemed incoherent, at least when understood “with the expected traditional mode of hierarchic composition”.

But “a more attentive reading [that is, Schapiro’s own!] has disclosed a sustained relatedness in the forms, with many surprising accords of the supposedly disconnected and incomplete parts.” (p. 41) I can’t here attempt to summarize Schapiro’s brilliant, lengthy analysis (see Schapiro (1977), pp. 102-30), except to note that Schapiro was driven to introduce and conceptualize a kind of artistic organization unknown by the main lines of European thinking on ‘composition’ (for which generally see Puttfarken (2000), and with regard to landscape in particular see Barrell (1972)), a kind he called ‘discoordinate’, understood as “a grouping or division such that corresponding sets of elements include parts, relations or properties which negate that correspondence. A simple example of a discoordinate design is a vertical figure in a horizontal rectangle or a horizontal figure in a vertical rectangle” (Schapiro (1977), p. 104). Without too much strain one might also understand Wollheim’s accounts of Jacob van Ruisdael’s use of detail--the crucially important small thing within the empty space next to the full and attention-catching space--as refined instances of non-hierarchical and seemingly self-subverting or self-contradicting discoordinate organization.

My invocation and brief summary of Schapiro’s great essay is in no way meant to diminish the originality and brilliance of Wollheim’s discussions of pictorial organization; rather it is my hope that it will aid in the understanding of Wollheim’s thought and relieve something of its appearance of idiosyncrasy. Likewise my summary of Wollheim’s account of artistic meaning is meant to show how his work on pictorial organization is part of a much broader intellectual project, one which issued in the greatest twentieth-century philosophical account of an artistic medium known to me.

References and Works Consulted:

John Barrell, The idea of Landscape and the Sense of Place 1730-1840: An Approach to the Poetry of John Clare (1972)

Michael Podro, Depiction (1998)

Thomas Puttfarken, The Discovery of Pictorial Composition: Theories of Visual Order in Painting 1400-1800 (2000)

Meyer Schapiro, ‘On Perfection, Coherence, and the Unity of Form and Content’, in Theory and Philosophy of Art: Style, Artist, and Society (1994)

--‘The Sculptures of Souillac’ (1939), in Romanesque Art: Selected Papers (1977)

Richard Wollheim, ‘The Art Lesson’, in On Art and the Mind (1974)

--Art and Its Objects (2nd edition, 1980)

--Painting as an Art (1987)

--The Mind and Its Depths (1993)

--‘Pictorial Form and Pictorial Organization’, ‘On the Question ‘Why is Painting an Art?’’, and ‘The Core of Aesthetics’, in Uncollected Writings: Writings on Art (2025)