As I indicated at the conclusion of my previous post, I turn now to the question of how contemporary criticism of the arts might be improved. But first, why should we think that criticism stands in need of improvement? Both Sean Tatol and Ben Davis appear to think that contemporary criticism of the visual arts is afflicted by a kind of collective failure to offer ‘judgments’. Already twenty years ago the art historian James Elkins had offered a similar diagnosis. What then is a judgment? If I understand the complaint, a ‘judgment’ is an evaluative statement made by a critic, whether explicitly or implicitly in a manner that can readily be made explicit, of the goodness or badness of an artwork or of an exhibition or of an artist’s oeuvre. In its simplest recognizable form, it’s ‘X is good (or bad)’. If one then asks, ‘Good in what sense(s), and relative to what?’, the negative responses are more evident: Tatol thinks that the relevant judgment of a critic is not to say that a work is good because it seems to express and endorse the sort of flabby liberalism of the New York Times or of ‘social justice’-type sentiments generally; whereas Davis thinks, very much in line with the contemporary consensus, that the critic should not judge a work good because it merely seems to exhibit to a high degree the kinds of skill and meaningfulness characteristic of ‘Western’ or mainstream modern or contemporary art. For both, again, a critic’s judgment should be the expression of the critic’s ‘mature’ sensibility, whether maturity is understood as the achievement of a process of self-education of the critic’s sensibility through encounters with canonical works in ‘best of’ lists (Tatol), or as the successful expression of the application of the virtue of curiosity to work’s outside of the critic’s customary range of interest and experience (Davis). So, finally, for both the lack of ‘judgment’ in contemporary arts criticism is the mark of immaturity, and so of a lack of personal-cum-cultural seriousness. Is this pervasive condition a crisis, as Elkins had already suggested early this century?

I don’t doubt that Elkins, Tatol, and Davis are right in noting a lack of ‘judgment’ in contemporary visual art criticism. However, I’m unmoved by the thought that this lack is a crisis, and further that the crisis might be dissipated by a return to critics routinely ‘judging’ the works they discuss. It seems to me that there are many considerations and reasons that count against the diagnosis of ‘lack-of-judgment’. One familiar point from the history of the philosophy of art is that the idea of criticism as partially though significantly consisting of ‘judgments’ strikes me is an unworkable throwback to the idea that there is a sharp distinction between ‘facts’ and ‘values’, and more particularly to something like mid-20th century emotivism, where philosophers imagined that statements could be cleanly divided into the factual and the expressive; the equivalent distinction with regard to art criticism would be between the descriptive and the evaluative/judgmental. As numerous philosophers have shown (Dewey, MacIntyre, Cavell, Putnam, etc.), the emotivist distinction between purely descriptive statements and merely evaluative statements collapses upon examination in both the realms of ethics and aesthetics. How, for example, could one sort out the descriptive and the evaluative in an aesthetic observation such as ‘his hesitant movements, connected in that passage with sudden dips, take on a peculiar poignancy against the slow-motion torso twists of the other four dancers’? As I suggested in a previous post, Isenberg’s formulation of the core of an act of art criticism as consisting of three moments—V (verdict); R (reasoning, including descriptions); N (norm)—is itself of a piece with emotivism if V, R, and N are treated as conceptually distinct and separable moments; the moments would then float free of each other, with R becoming purely descriptive, and V and N both purely evaluative, distinguished only by their sources of the individual uttering V and some collective sustaining and institutionalizing N.

One way that suggests itself to capture the force of Tatol’s and Davis’s complaint about lack of judgment, without relying upon problematic emotivist conceptions, would be to reframe their point as rather a lack of consideration of the point of the artwork. For both the lack of judgment indicates the incompleteness of the criticism. So instead of tacking on a judgment, the critic might consider the point or points of the piece, that is, what it aims to accomplish and whether it does so, but also the quality of the aim, whether the aim is worth accomplishing: whether, for example, the work is sufficiently capacious or responsive to recent art or in touch with current audiences.

A second attractive feature of replacing ‘judgments’ with ‘questions of worth’ is that the latter, but not the former, is integral to the practice of the arts. To see what this involves and how it might matter, consider the philosopher Paul Woodruff’s account of theater. Woodruff proposes a broad conception of the art of theater as “the art by which human beings make or find human action worth watching, in a measured time and place.” (Woodruff, p. 18) As Woodruff notes, this is an inclusive definition, or beginning of a definition, in that it counts the spectacle of “a frisky Christian . . . fight[ing] off a lion” as theater, though it excludes as non-theatrical watching a comatose Christian being devoured by a lion” (no human action there), as well the typically less sanguine activity of bird-watching. (p. 19) This simple proto-definition immediately raises the question of what makes something worth watching; Woodruff responds by noting first that ‘being worth watching’ is mostly a matter of finding and presenting human characters worth caring about, and that this is of a piece with our psychological need to give attention to and to be the object of attention of others. (p. 22) The art of theater then has as part of its elements and mechanisms the ways in which we capture the attention of others. This can be done well or poorly. (p. 24) Theatrical art tries to solicit and engage the audience’s emotions, and to do so in a way that contributes to what Woodruff calls ‘cognitive empathy’ or, simply, understanding. (pp. 181-83) Theater is good to the degree that engages emotions and cognitive empathy, bad to the degree that it fails to so engage, or to engage them in such a way that emotions and cognitive empathy conflict with, obscure, or undermine each other. (pp. 179-80) Now, if we were to approach and conceptualize the visual arts in something like Woodruff’s manner, we might first offer a proto-definition of such arts as ‘artifacts that exhibit visual interest that is worth looking at’, and mutatis mutandis with the other points from Woodruff’s explication. On such an account of visual arts, the aim of art criticism would be to draw the reader’s attention to what is of visual interest, that is, of what is worth looking at; further, art criticism supplies anything and everything guides and educates the viewer towards the points of visual interest, and then intensifies that viewer’s emotional and cognitive engagement with the work. Adopting a Woodruff-like account of the visual arts would in our context throws light on another problem with the ‘judgments’ advocated by Tatol and Davis: their conception of detachable ‘judgments’ misses the ways in which critics’ evaluations are necessarily rooted in the critic’s understanding of the nature of the art form and its characteristic mechanisms for soliciting the audience’s engagement and sense of worth. Instead of art criticism consisting of something like a factual description, an invocation of relevant norms, and a judgment, art criticism is the expression of an ongoing engagement with an art form, the recognition of its history, mechanisms of meaningfulness, and characteristic values, and some sense of the relative poverty or richness, and the relative harmonization or discordance, of how a particular new work takes up these resources.

A third attractive feature of replacing the question of judgment with the question of worth stems from the tighter connection between the latter question and some characteristic contents of a piece of art criticism. Judgment floats free of description; and, since norms do not apply themselves, but rather are applied by the critic guided by her sense of relevance and importance, any judgment in art criticism is necessarily under-determined: it requires further acts of ‘judgment’ to determine what norms should be applied, and how to apply them. Isenberg’s schema, with its schema shaped by the background emotivist assumption of a sharp division between fact and value, or description and norm, is silent on this, and so misses the sense in which judgment is not an isolable moment of art criticism. As with Tatol’s and Davis’s complaints, contemporary critics may neglect or suppress the judgment of goodness or badness, but on pain of engaging in an altogether different activity they cannot avoid ‘judging’ the relevance and pertinence of the descriptions they offer and of the norms they invoke. Pace Isenberg, Tatol, and Davis, there is nothing in a piece of art criticism that is not a piece of judgment. Orienting criticism to the question of worth, by contrast, avoids the fiction of an isolable and distinct judgment. If a critic writes about a piece at any length greater than a single sentence, the critic de facto asserts that the piece is worth looking at, and again the question immediately arises as to why and in what ways and senses it’s worth looking at. Now, if the piece discussed is or is presumed to be an artwork, one question that also immediately arises is how fruitfully to place the work in the history of art and the arts. And this question points us to the great importance of among other things analogy and metaphor in art criticism.

In an analogy one says ‘X is like Y in such-and-such ways’. A metaphor (‘A is B’, where the sentence ‘A = B’ is spectacularly false or trivially true (‘Juliet is the sun’; ‘No man is an island’)) is similar to an analogy in that in both cases the referent of one term (Y or B) is treated as relatively well-known and relatively determinate, and aspects of those terms’ characterization are mapped onto a relatively poorly known and less determinate referent of the other term (X or A). In the typical use of analogy and metaphor in art criticism, it is the artwork itself, or some aspect of the piece, that is treated as relatively indeterminate, and the critic draws a term from the presumed cognitive stock of the audience and applies it to the artwork. So a critic might say: ‘the painting is a window onto a bourgeois interior’ or ‘the surface is like a patch of parched skin with its cracks, creases, and boils’ or ‘the installation is a dungeon wherein the viewer finds herself oddly at home’. Now, as James Grant has argued with regard to metaphor, two major reasons that this figurative language is prominent in art criticism is that are that the critic wishes to capture the attention of the audience, and that the reader’s induce effort in imagining and understanding the figurative language offers a kind of engagement analogous to the imaginative work of seeing the piece in person, and perhaps also the imaginative work of making the piece itself. It is hard to see how the addition of ‘judgment’ in Tatol’s and Davis’s sense would similarly induce the a reader’s imaginative participation in an artwork. There is perhaps no close connection between raising the issue of whether a work is worth seeing and the use of analogy and metaphor in criticism, but asking in what ways and senses the work is worth seeing would seem to lend itself more to vivifying the work for a reader than pronouncing a judgment upon it. A judgment is summative and definitive; the question of worth is open-ended, and subject to revision in light of new contexts and concerns.

How might art critics’ uses of analogy and metaphor be part of the practice of art criticism oriented towards the question of ‘worth’? Recall Monroe Beardsley’s remark that in viewing recent art one often has the sense of seeing a ‘one-off’, something striking and strikingly unfamiliar in its materials, manner of handling, and point. Contemporary art prominently contains among other things works consisting of used tires, of paint dripped in a line, a pile of candy, and so forth. Beardsley suggests that such works defeat criticism in its usual practice and purpose. But also recall Richard Wollheim’s remarks about what he calls the ‘bricoleur problem’. Claude Lévi-Strauss has proposed the distinction with regard to the design and meaning of artifacts between an engineer and a bricoleur, where the former generates and design and working specifications prior to the construction of an artifact, and the latter takes up whatever heterogeneous materials are at hand to improvise and cobble together into a work. The bricoleur problem is to understand how a work, made without a plan and without prescribed ingredients, gains intelligibility and meaning. Wollheim remarks that with regard to artistic making and artistic meaning, there are two basic and different situations. (Wollheim 1980) Much of the world’s art is part of an established art form: drawing, painting, sculpture, and so on. As Kant remarks, artworks are not the products of strict application of rules; but they are nonetheless typically instances of some genre, some sub-genre, and some tradition(s) of making and viewing, and a suitably attuned viewer can reliably place such works in their relevant genres and traditions, and thereby have a rich and focused set of expectations of how to engage with the work. The other situation is when an art form or genre begins: how does, say, the first drawing, the first Greek tragedy, the first piece of video art gain intelligibility and meaning? This is the acute problem of the bricoleur, who uses materials in the absence of inherited and accredited ways of working them. Wollheim suggests that a primary way in which both the artist makes novel works meaningful and the audience comes to find such works meaningful will be through the use of analogies, in particular analogies between the new work and prior artworks and art forms. If so, this suggests how to relieve Beardsley’s remark of its sting: the ‘one-off’ will be made and understood in terms of some prior works. The audience will not be utterly disoriented in the face of novel works, as the art critic can propose and explicate some relevant analogies. The use of analogies, then, facilitates the transfer of worth from established art forms and exemplary artworks to contemporary pieces.

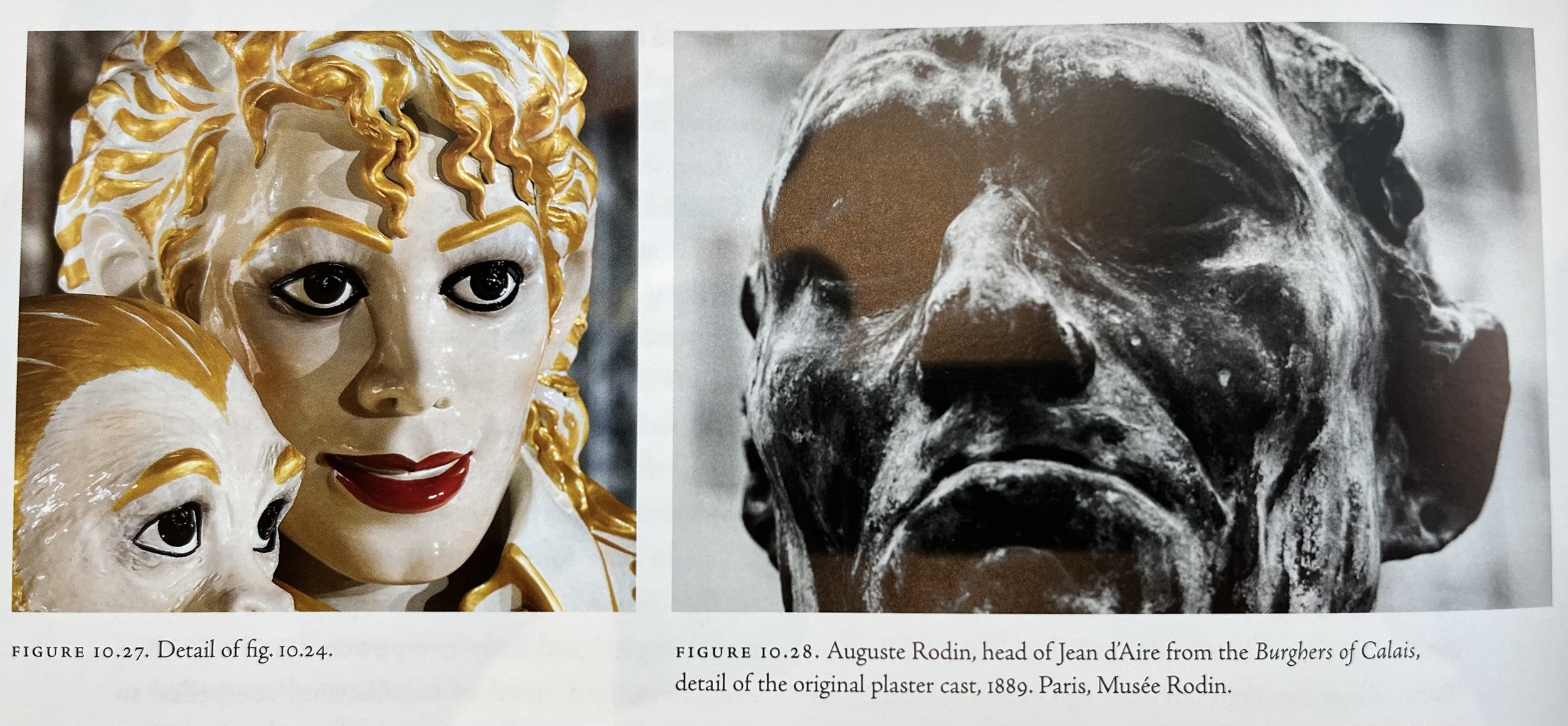

Important roles for metaphor in art criticism differ somewhat the central role of analogy as a response to the bricoleur’s problem because, I would suggest, metaphorical meaning is a fundamental part of artistic meaning generally. One version of this claim was advanced by Arthur Danto with the thought that a work of art is always a metaphor for the viewer herself. Danto attempts to explicate this with Hamlet’s thought that the plays the thing wherein one might catch the conscience of a king: one sees (aspects of) oneself in an artwork. I mention Danto’s account because it is given in the single most influential book in the philosophy of contemporary art, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace; but I have never been able to work out his suggestion to my satisfaction, and it is no part of what I mean. Rather, I would suggest, along the lines introduced by Wollheim in his Painting as an Art, that a major way in which artists build meaning into their works is by introducing and/or developing metaphors for their works and its parts. One kind of such metaphors are the basic ones that prevail in different eras, such as ‘painting is window’ in the Renaissance, ‘painting is material object’ in Modern art, and ‘painting is commodity’ in Contemporary art. A second kind arises when artists metaphorize parts of their work, such as ‘canvas is skin’ (Titian) or ‘brushstroke is furrow’ (Van Gogh) or ‘paint is gesture’ (Pollock) or ‘paint is cosmos’ (Pollock again). The invocation and description of both kinds of metaphor, especially the first, would likely induce some of the effects noted by Grant in criticism, and additionally carry something of the sense of inheritance of past and recent kinds of worth into the criticism of contemporary artworks.

To conclude, I’d like to make a final and perhaps highly controversial suggestion on the superiority of orienting art criticism to worth as opposed to judgment. Davis urges that re-introducing judgment into art criticism, along with Tatol’s use of a rating system, has the signal merit of ‘getting people talking’ about contemporary exhibitions, especially of smaller or relatively modest shows that would not be otherwise reviewed or widely discussed. But what sort of talking is this, if as Davis suggests the judgment declares the show good (or bad)? Issuing such judgments invites disagreement, and especially one might think of the disagreement so prominent on social media, where positions rapidly polarize and harden, and yeas and nays become purity tests for in- or out-group membership. Davis mentions that most art that is shown is, almost be definition, mediocre. Is it plausible to think that regularly issued judgments of mediocrity would be an important part of a restored public sphere? If one reflects on what sort of art criticism has as it were survived the test of time, that is, remains worth reading for later generations, it seems to me irresistible to think that such criticism arises when a critic articulates the distinctive poetics and values of a novel or underappreciated art form. Among many examples of such I would include Gilbert Seldes on Krazy Kat, C. L. R. James on Dick Tracy comics, Edwin Denby on Balanchine, Robert Warshow on Hollywood Westerns and gangster movies, Meyer Schapiro on Romanesque portals and statuary, and Leo Steinberg on Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Seeking value and articulating new kinds of poetics and modes of engagement is perhaps a worthier occupation than issuing judgments.

Monroe Beardsley, ‘What are Critics For?’ (1978), in The Aesthetic Point of View:

Selected Essays (1982)

Arthur Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (1981)

Ben Davis, ‘Negative Reviews? Part 1 & 2’ in Artnet (2023)

Edwin Denby, Dance Writings (1986)

James Elkins, What Happened to Art Criticism? (2003)

James Grant, The Critical Imagination (2013)

C. L. R. James, The C. L. R. James Reader (1992)

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment (1790)

Arnold Isenberg, ‘Critical Communication’ (1949) in Aesthetics and the Theory of Criticism (1988)

Claude Lévi-Strauss, La Pensée Sauvage (1962)

Elaine Scarry, Dreaming by the Book (1999)

Meyer Schapiro, The Sculpture of Moissac (1985)

Gilbert Seldes, The Seven Lively Arts (1924)

Leo Steinberg, Other Criteria: Confrontations with 20th Century Art (1972)

-----‘Art Minus Criticism Equals Art’ (2002) in Modern Art (2023)

Sean Tatol, ‘Negative Criticism’ in The Point (2023)

Robert Warshow, The Immediate Experience (1962)

Richard Wollheim, Art and its Objects (1980)

-----Painting as an Art (1987)

Paul Woodruff, The Necessity of Theater (2008)

Postscript: In previous posts I promised that I would consider some of my own work as instances of the kinds of art criticism I recommend. That promise has been broken, for now. These posts on Tatol and Davis are meant for myself to be part of working out issues that I hope to address in an introduction to a short book of my selected criticism. The promise shall be fulfilled then.